Mike Lynch: Flown to the US in chains, now he is free … and talking

This interview was first published on July 27, 2024.

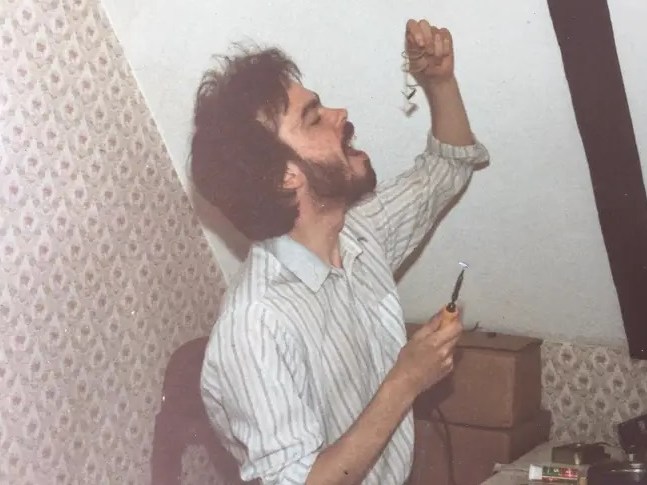

A shin-high Shetland sheepdog bounds out of the front door of a grand, ivy-covered terraced house in Chelsea, west London, intent on striking fear into whoever has rung the courtyard buzzer. Running in circles, its high-pitch barks are entirely unconvincing. Mike Lynch, the 59-year-old British tech tycoon, beams from the doorway like a proud father. “All right, all right,” he says, chuckling. “He’s harmless.”

Lynch is a dog lover. He and his wife, Angela Bacares, have six: two dachshunds and four sheepdogs. But this one, Faucet, is special. For more than a year Lynch, known as “Britain’s Bill Gates”, and Faucet were under house arrest in America.

Lynch was extradited from Britain in May last year and spent 13 months under house arrest in San Francisco as he awaited trial on 17 charges of conspiracy and wire fraud — later reduced to 15 charges — brought by the US Department of Justice. If convicted, Lynch, with an estimated net worth of £500 million, faced up to 25 years in a US prison, where, given his age and a serious lung condition, it was unlikely he would have lived to see freedom. “I have various medical things that would have made it difficult to survive,” he says, settling into a tastefully appointed sitting room that is far removed, in every respect, from the hard wooden benches of the California courtroom where his fate hung in the balance.

• Mike Lynch cleared on all charges over Autonomy deal in US fraud trial

The case stemmed from what should have been Lynch’s crowning achievement: the $11.7 billion (£7.4 billion) sale in 2011 of Autonomy, the business software company he co-founded, to the American tech giant Hewlett-Packard (HP). The deal turned the father of two — whose daughters were nine and six at the time — into one of Britain’s richest people. But within a year HP, which refers to itself as Silicon Valley’s original start-up, founded in a garage in Palo Alto in 1939, claimed that he had cooked the books, and thus tricked it into paying $5 billion more than it should have for a company packed to the gills with fake sales and all manner of financial jiggery-pokery.

So began a 12-year transatlantic legal fight that led to Lynch’s extradition. As he contemplated the end of life as he had known it — science adviser to David Cameron as prime minister, recipient of an OBE for services to enterprise in 2006, status as one of his generation’s brightest minds — Faucet was by his side the whole time. They now seem almost surgically attached.

“The problem is this,” he says, gesturing to the pup that has leapt on to the couch as soon as Lynch sits, propping itself against his neatly pressed slacks. “We spent all our time together, so he wants to be here all the time. He still sleeps on the pillow next to me.”

His chances of winning were infinitesimal. Less than 0.5 per cent of federal criminal cases in America end in acquittal. And there was potentially damaging legal precedent: Sushovan Hussain, Autonomy’s former finance director, had already been convicted for his part in the same alleged crime. Hussain, who was born in Bangladesh and came to Britain when he was seven, was sentenced to five years in prison by Charles Breyer, the eccentric, bow tie-wearing San Francisco judge who would also hear Lynch’s case. Hussain, who started his sentence at the Allenwood penitentiary in Pennsylvania, returned home to Kent in January, before Lynch’s trial kicked off in March.

And in 2022 a British High Court judge ruled in a civil case brought by Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE), one of the two companies HP split into in 2015, that Lynch had in fact defrauded the company. Mr Justice Hildyard is expected to rule on damages before the end of the year.

On June 6, however, Lynch beat all the odds. After a 12-week trial in the wood-panelled courtroom on the 17th floor of the San Francisco federal building, he was acquitted by a jury on all counts. When the jury foreman read out “Not guilty”, Lynch cried. So did his wife, who sat in the front row of the gallery for the entire proceedings. So did several of the young lawyers on Lynch’s legal team.

• Bayesian yacht sinks: Mike Lynch ‘missing’ in freak Sicily tornado

From the day HP went public with its allegations, Lynch had always maintained his innocence, arguing that he was being railroaded by a powerful American corporation stricken with a severe case of buyer’s remorse. It took more than a decade and $30 million in legal fees to get someone finally to agree with him, and just like that Lynch was free.

In his first interview since the verdict he recalls that life-altering moment. “When you hear that answer, you jump universes,” Lynch recalls, emanating a mix of defiance and disbelief. “If this had gone the wrong way, it would have been the end of life as I have known it in any sense.”

Now the court-ordered armed guards who had been with him 24 hours a day could be dismissed. He could remove the ankle tag and escape the gaze of the surveillance cameras that had been installed in every room of the San Francisco mansion to which he was confined. He was given back his passport and the $100 million he had handed the federal government as collateral to prevent him from fleeing.

He could see his daughters, who are now 21 and 18, return to his beloved farm near Aldeburgh in Suffolk and greet his dogs, all of them named after engineering parts: Switch, Tappet, Pinion, Valve, Cam. As Faucet was acquired to keep him company in San Francisco, Lynch gave him an Americanised name.

And now, in the sitting room of his west London pile, Lynch appears to be a man still grappling with his new reality, a cork bobbing on an ocean of relief. “It’s a very strange situation to now be in a different mindset where you’re back,” he says through tears. “I stood on Piccadilly Circus the other day, which has the most enormous permanent traffic jam, and I’m just thinking, ‘This is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.’ ”

So what does he do now? One project he feels deeply passionate about is the one-sided extradition treaty between the UK and the US. “It has to be wrong that a US prosecutor has more power over a British citizen living in England than the UK police do,” he says. He is also keen to fund a British equivalent of the Innocence Project, the American nonprofit organisation dedicated to freeing people who have been wrongly convicted. “The system can sweep individuals away. There needs to be a contrarian possibility that’s saying, ‘Right, well, the whole world thinks you’re guilty but, actually, was that a fair conviction?’ ”

For the moment, though, he is concentrating on doing nothing. “You don’t realise how tired you are until you stop and have a chance to be tired,” he says. “It is that sort of exhaustion in your bones.”

What he has been doing, however, is contemplating a mountain of what he calls “Saint Peter questions”. He explains: “So you arrive at the Pearly Gates before being dispatched to the elevator down to the basement, and you say to Saint Peter, ‘You know, just before I go, what was that all about? What was that?’ ”

It was August 18, 2011, and Mike Lynch was on top of the world. “This is a momentous day in Autonomy’s history,” he declared. He had just unveiled the blockbuster sale of Britain’s biggest tech company. “From our foundation in 1996,” Lynch said, “we have been driven by one shared vision: to fundamentally change the IT industry by revolutionising the way people interact with information. HP shares this vision.”

It was the culmination of an unlikely trajectory that began in Ilford, east London, where Lynch grew up as the son of Irish immigrants. “You had to learn to run fast,” he says. His mother had emigrated in the early 1960s and worked as a nurse. Lynch’s first job was as a cleaner at the same hospital. “I’m still a demon mopper,” he says. “There’s an art form to it, you know.”

A gifted student, he earned a scholarship to Bancroft’s School in Woodford, east London. He did well enough to win a spot at Cambridge University, where after a degree in natural sciences he earned a PhD in signal processing, used to detect patterns in vast sums of data — a precursor to today’s artificial intelligence systems. A boffin at heart, he stayed on as a research fellow, and in 1996 launched Autonomy. At the time the company was just a handful of “eccentric people working really hard on a project. No bureaucracy. No admin. Lots of late nights, lots of eating cold pizza.”

By the time HP came calling 15 years later, Autonomy was the most valuable tech firm in Britain, employing 2,000 people across 20 countries. Some of the world’s largest companies, such as AT&T, BNP Paribas and BlackRock, relied on its software to make sense of their mountains of data.

Lynch was an intense and driven boss. He pulled off countless takeovers, gobbling up competitors and growing the business ever larger. He clashed with critics. Daud Khan, a City analyst who was among the first to publicly question Autonomy’s accounting practices, said Lynch waged a “vendetta” against him, banning him from Autonomy investor calls. Khan testified in the US and UK trials. Lynch has denied having a vendetta against him or any of his critics. The High Court judge in London called Lynch a “blunt and dictatorial” executive who “expected to get his way, and did so”. Lynch admits he was “hard-charging”, but that such an attitude is required to build a big business. No one could deny that he had built Autonomy into what appeared to be that rarest of birds in corporate Britain: a homegrown tech success story.

Leo Apotheker saw salvation in Lynch’s empire. The softly spoken 57-year-old German chief executive of HP was under immense pressure. He had taken over the year before with a mandate to save a fading Silicon Valley giant. As Apple’s iPhones and iPads sold like hot cakes, HP rolled out laughably clunky rival products that few people bought. Sales of its printers and PCs had gone into reverse. So Apotheker made a bet: he would break up the 72-year-old behemoth, jettison the PC arm and buy Autonomy. In so doing he would transform HP into a seller of business software, which, by its nature, delivered far fatter profits in a fast-growing market.

So desperate was Apotheker to buy Autonomy, he paid a 64 per cent premium — the percentage mark-up over a company’s stock market value. That was twice the typical rate that London-listed companies sell for. It was an offer that, under UK takeover rules, Lynch was duty-bound to recommend. “One of the great mythologies was that I had a choice to sell,” he says. “It would have been like trying to stop a herd of elephants.”

The deal turned many of Autonomy’s longest-serving employees into millionaires, and meant a $516 million payday for Lynch with his 8 per cent ownership stake. But he didn’t plan to cut and run. He had agreed with Apotheker to stay on and head the new division.

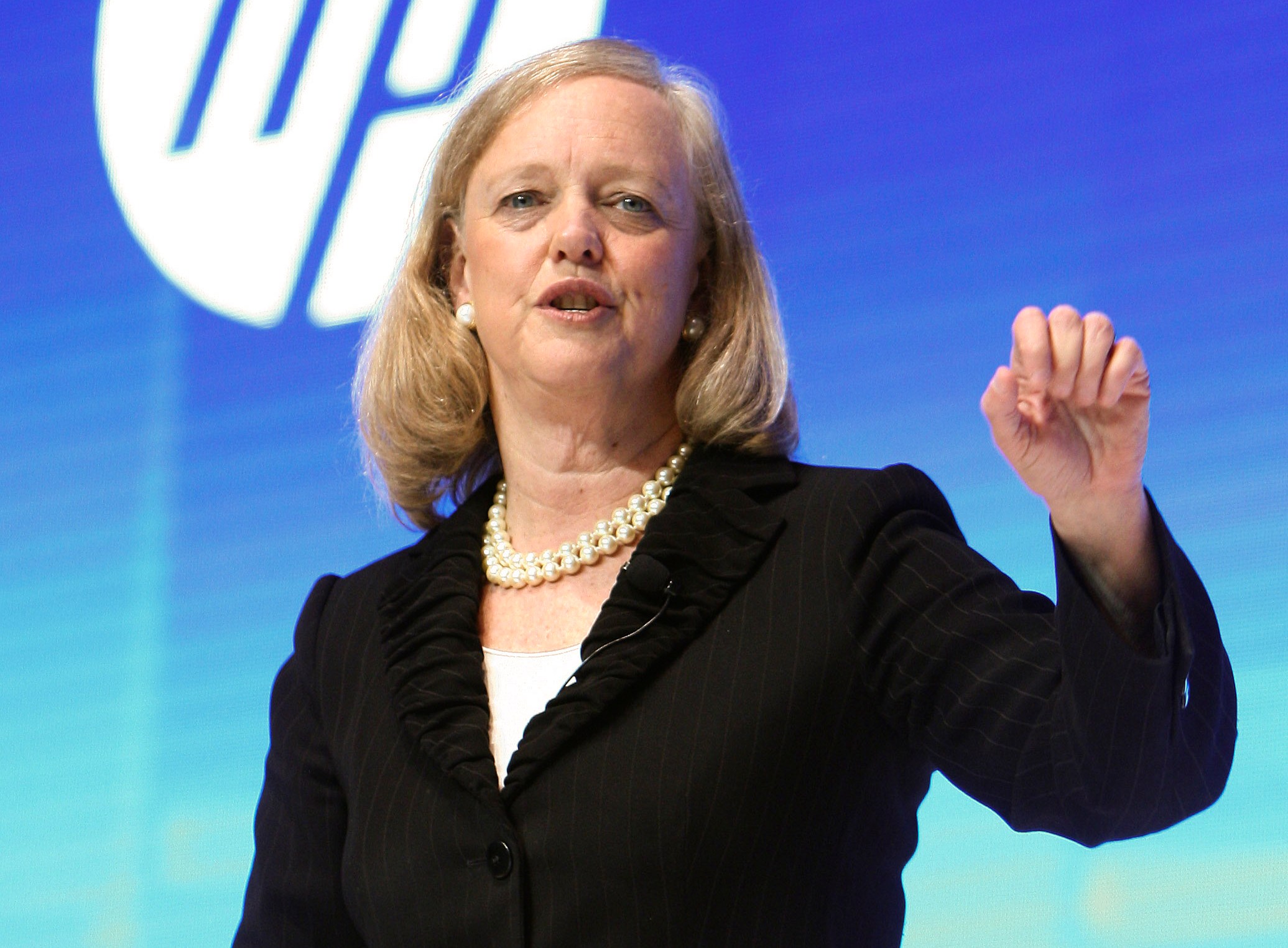

HP investors, though, hated Apotheker’s plan. The shares tanked and just five weeks after announcing the takeover Apotheker was fired. He was replaced by Meg Whitman, the 55-year-old rock-star tech executive who had just spent $140 million of her own money only to lose a painful race for California governor. “Suddenly we were the unwanted stepchild,” Lynch says.

HP was in worse shape than perhaps Whitman had appreciated. Six months after the deal closed she fired Lynch, along with 27,000 HP workers. Hundreds of Autonomy employees had also begun to leave because HP failed to deliver them promised share options.

Even in the best case scenario, the Autonomy takeover was “high risk, high reward”, Lynch admits. Getting rid of its key architects, as well as the entire Autonomy executive team, doomed it to failure.

Lynch recalls the day he realised that this was going to be complicated. “I was in London and this message comes through on my phone that they’ve written Autonomy down. This didn’t surprise me because I knew from the grapevine they had lost all the good people,” he says. (A writedown is when a company reduces the value of an asset on its books, in the same way a home’s value can plunge if, say, the market crashes or the roof blows off.) “And then the second message came through: they were blaming the accounting. I remember thinking, ‘This is insanity.’ I naively thought that about three weeks later there would be some sort of ‘we didn’t mean that, we meant this’. And it would all be done. Boy was I wrong.”

That afternoon HP announced a huge $8.8 billion writedown, admitting that it had, in effect, paid four times more for Autonomy than it was worth just one year later. But this was not just a deal gone bad. HP claimed to have uncovered large-scale fraud at Autonomy, alleging that “serious accounting improprieties” accounted for more than $5 billion of the lost value.

Against the advice of his PR handlers, Lynch went on TV that day to defend himself. “The scariest thing I’ve ever done in my life was to go on Channel 4 News live when this broke,” he says. “HP cut us off at the knees, but they didn’t kill us.”

The US Justice Department opened an investigation, as did the UK’s Serious Fraud Office. The SFO would drop its case in 2015 for lack of evidence, but HP, having gone public with its explosive claim, went in for the kill. According to court documents it devised a detailed PR plan called Project Sutton to make sure key journalists, politicians and regulators knew that Autonomy, and by extension, Lynch, were to blame. The plan involved convening a “truth squad” of HP employees to monitor stories, feed documents to reporters detailing the alleged malfeasances and “preserve the credibility” of Whitman, who was thought still to harbour political ambitions. Among Whitman’s jobs was to personally write to the prime minister, David Cameron, lest HP lose any key government contracts in Britain.

“This case is going to be great for future scholars,” Lynch says. “You have ‘How to run a PR smear campaign in 2012’. You can get the documents now and look at how it was done.” He adds: “It was like being hit with a tsunami. We were always playing catch-up.”

The slow-rolling legal fights that followed took a toll. Lynch’s brother, a builder, died while Lynch was confined in San Francisco, so he missed the funeral. His mother also died before the trial. “They never lived to see this resolved,” he says ruefully.

His daughters didn’t know any reality other than the one where their father has been publicly labelled a crook and that he may spend the rest of his life behind bars. “I remember early on sitting them down and the analogy I gave my six-year-old was that Daddy had sold someone a plant. They hadn’t watered it, it had died, and they were trying to blame Daddy for this,” he says. Now 21, she has followed in his footsteps and is reading physics at Imperial College; her 18-year-old sister will study poetry next year at Oxford.

“There was a long period when they thought I would somehow fix this, but the nearer we got to the date, the more they understood that this was a battle.”

The Metropolitan Police handled his forced removal last May in a rather British manner. Instead of walking him out of his Chelsea home in handcuffs, they allowed him to meet them round the corner. The Americans were very American. As soon as the US Marshals took Lynch into custody at Heathrow, they put him in chains and bundled him on board a United Airlines flight, stuffing him in the back row before anyone else boarded.

They handed him a San Francisco Giants cap to help shield his identity and draped a coat over his shackles. “Once you’re handed into American custody you’re in a completely different world,” Lynch says. “It’s ridiculous. You’re in chains, even though, like, what are you going to do? As you can see, I’m not exactly an Olympic boxing champion.” Indeed, as the saga has worn on, Lynch’s closely cropped hair has greyed, his waistline has expanded. It all looked rather bleak. “I’d had to say goodbye to everything and everyone, because I didn’t know if I’d ever be coming back.”

However, he had a few factors in his favour. One was Sushovan Hussain, his No 2 at Autonomy, who, unwittingly, had acted as a sacrificial lamb. By studying Hussain’s hearing, Lynch’s legal team could see in detail the government’s case and devise a better plan to defend against it. “It’s very sad that Sushovan had to go through that,” says Lynch, who remains friendly with his former colleague. “But, yes, it was certainly a benefit to us to have seen what was coming.”

US prosecutors had ploughed through more than 16 million documents and from that trove pulled out tens of thousands that purported to show how Lynch and Hussain had, together, “used every accounting trick in the book” to boost Autonomy’s earnings. Having a sense of which documents prosecutors would use and how they would use them provided a critical leg-up.

Even so, Lynch was filled with forboding. “With the low acquittal rate in the US, plus the fact we’d seen all the methods used, we were not hopeful,” he explains. To stay sane, he says, he would, “never watch anything with prisons in it”. He coped by staying laser-focused on the task in front of him — the hour-by-hour proceedings and preparations for trial — and pushing away thoughts about what everyone agreed would be the likely outcome. “I have a saying, ‘First tiger on the path.’ If you’re walking down the path and there’s multiple tigers, there’s no point in worrying about tiger number four. You have to worry about tiger number one.”

But one can only think about tiger avoidance for so long. What did he do when he wasn’t meeting with his lawyers or trawling through documents? “I’ve always played tenor sax, so I took the opportunity of house arrest to move over to the alto.” He watched the Super Bowl with his security detail, with whom he became “great friends”. He adds: “They turned out to be the most wonderful people. I miss them now.”

Lynch had another factor in his favour: the nature of the case. The Department of Justice had to communicate a simple idea — that Lynch was bent — but do so via a plodding, painstaking parade of emails chockful of jargon, financial reports and spreadsheets, where single cells would be the subject of lengthy interrogation. It made for a wildly boring and turgid trial. The jurors often seemed glassy-eyed. One was dismissed because he repeatedly fell asleep. In short, the prosecutors’ tale of financial skulduggery, unspooled in spreadsheet after spreadsheet, didn’t quite land.

That is not to say there weren’t plenty of transactions that raised eyebrows, such as “round trip” contracts in which Autonomy would pay a company for “services” and then swiftly sell that same company software for a similar sum. The allegation was that Autonomy was, in effect, funding its own sales to make its business look more healthy than it was. This was one of countless ruses Lynch oversaw, prosecutors claimed, to inflate sales and then, on his orders, lie to its auditor, to City analysts and to regulators about the true state of the business.

Lynch admitted in court that Autonomy “wasn’t perfect”, but said that he operated above the plane where any misdeeds might have transpired, and that any questionable activity was entirely immaterial in the context of a thriving business that was bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars a year. He told the court: “There are people that cut corners that shouldn’t have. There are a thousand little realities. A lot of what we’ve been looking at is like peering through the door of a kitchen and seeing the sausage-making machine, and that’s how it really works. If you take the microscope into even the most spotless kitchen you’d find bacteria. If it wasn’t there, that’d be something very abnormal. I don’t think Autonomy was any different.”

His lawyers claimed that Autonomy’s books were approved by outside accountants and that, under British accounting standards, the deals in question were appropriately accounted for. The latter was a key point. Much of the trial was spent deep in the accounting weeds, examining subtle but important transatlantic differences. What might look fishy to an accountant in San Francisco could be totally above board to one in London, Lynch’s lawyers argued, and then produced experts to support that position. There was no fraud, argued Lynch’s team, just a difference of professional standards.

In week ten of the trial, after more than 35 people had taken the stand, there was one final witness: Lynch himself. It was a high-risk play. Few criminal defendants testify in their own defence because it exposes them to direct cross-examination. After weeks of being painted as a pantomime villain, however, the gambit humanised Lynch. And critically, when handed their golden opportunity, prosecutors instead subjected him to hours of perfunctory questions about a handful of transactions.

Lynch’s head lawyer, Brian Heberlig, hammered home this point in his closing argument: “This was the prosecutor’s moment to go right for the jugular with the best evidence he had to prove that Mike Lynch was guilty. What happened? You witnessed it. He reviewed a chronology of documents, with no probing questions.” He added: “It takes an exponential leap, not justified by the evidence, to conclude that Mike committed fraud.”

The jury agreed.

The San Francisco verdict scrambled a narrative that for many had long been settled: Lynch was guilty. Could it really be that he was innocent all along? And if he was, how did a corporate takeover gone bad turn into a decade-long nightmare that nearly destroyed a middle-aged dad’s life? Or was this simply a very American outcome, where a wealthy businessman pays for the best defence money can buy and walks free?

In 2022 the UK High Court judge, having heard 93 days of testimony in a civil trial, including 20 days when Lynch was on the stand, concluded that he and Hussain had committed fraud. Mr Justice Hildyard explained his reasoning in an excruciatingly detailed 1,700-page judgment. It began with the central question: “Fraud on a grand scale; or relentless witch-hunt?” He concluded that it was, indeed, the former. “In my judgment, Dr Lynch shared with Mr Hussain knowledge of the impropriety of the way aspects of Autonomy’s actual business activities had been accounted for and disclosed (or rather disguised, concealed or misleadingly presented),” he wrote. HPE is seeking $4 billion in damages from Lynch personally. The judge has already indicated any penalty would be far smaller.

He plans to appeal, but now the only jeopardy he faces is having to write a rather large cheque. And about that, Lynch, who advises and is an investor in several tech start-ups, is not worried. “My wife has been very good at investing in the things that I’ve told her to from a point of view of technology. We’ve done very well,” he says. “It’s not a perilous situation.” Beyond being his investing proxy, Lynch’s wife, Angela, has stayed assiduously out of the limelight. When approached in the hallways outside the courtroom she silently waved off requests for comment. For this interview at their London home she stayed behind in Suffolk. The first time she heard the particulars of the case, Lynch explains, was in San Francisco. “We made the decision that Angela would not be involved in the case. She stayed completely separate. Her focus was the family and children,” he says.

He points out that much of the High Court case was based on hearsay evidence directly lifted from Hussain’s trial in America, evidence that has now been undermined by Lynch’s lawyers. “So the big question that the lawyers are looking at is, now that we know that evidence wasn’t true, how does that affect the UK trial?”

• I focused on tech, not accounting, says Mike Lynch as he denies Autonomy fraud

In retrospect Lynch says the whole affair is rather easy to explain. Whitman, a politically ambitious tech millionaire, needed to reset after her disastrous run for Republican governor of California (she lost by 14 percentage points). HP, a company in need of a revamp, could have been her springboard. But it was in bad shape, and Autonomy, a deal she did not devise, made for a convenient scapegoat, he argues. “There’s this moment where suddenly they decide to blame [the writedown] on Leo Apotheker and Autonomy management,” rather than the failure to integrate two wildly different businesses and thus extract the billions of dollars of “synergies” that HP had promised its investors.

The snowball had begun to roll down the mountain, even as HP executives questioned whether they could pin the blame on Lynch. Damning internal documents, produced in the court case, show HP’s accountants struggling to justify the $5 billion fraud allegation, claiming that it would require “nonsensical” and “crazy” calculations. After HP went live with its version of events, one employee claimed the accusations were based on “spin and speculation”.

Lynch says: “I would love to say to [Whitman], ‘What were you thinking? Did you really think that that was going to just run?’ ” Is he not furious? “Anger,” he says, “is not fruitful. You just have to get on with dealing with the onslaught.” Whitman, now based in Nairobi as the US ambassador to Kenya, did not return requests for comment.

After 13 years, 16 million documents, three court cases, hundreds of millions of pounds in legal bills and contradictory outcomes, the answer to the question of “who is right?” is an impossible one. What is clear, however, after having spent years monitoring the case, days watching Lynch from across a courtroom and hours more in his sitting room, Faucet the dog nuzzled into his lap, is the sense that Lynch is emerging from something akin to a near-death experience.

“That is very much how I handled it,” he says. “It’s bizarre, but now you have a second life. The question is, what do you want to do with it?”

Post Comment