Attacks on Kamala Harris plan to ban ‘price-gouging’ are unfair

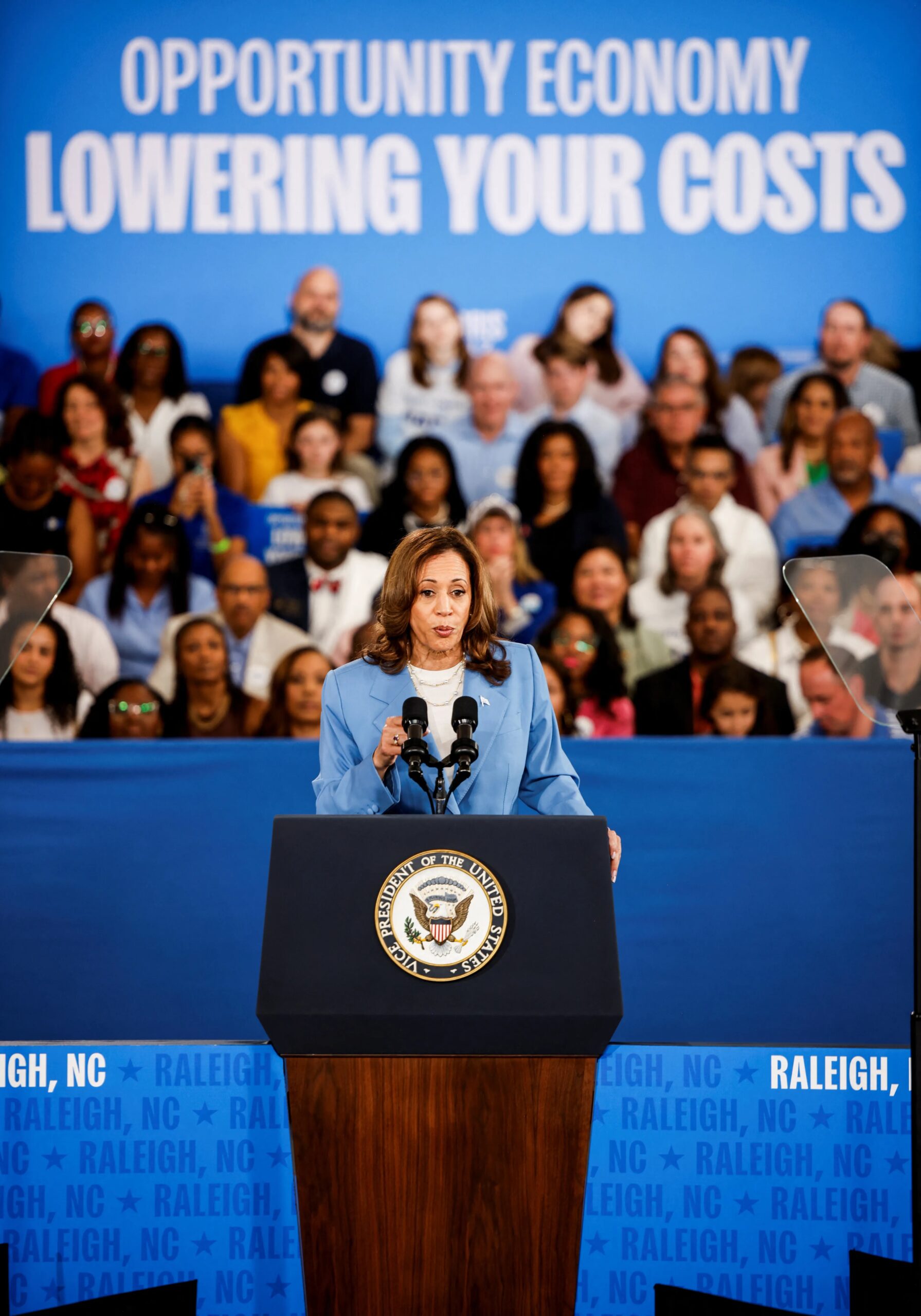

The two candidates vying to become president of the United States have started fleshing out their plans for the economy. Last week it was the turn of Kamala Harris, the Democratic nominee, who made her maiden economy-focused speech in Raleigh, North Carolina.

The incumbent vice-president focused squarely on measures to alleviate the cost of living crisis for Americans, a weak spot for the present administration during a campaign in which a majority of voters have said they favour the low-inflation years of Donald Trump, blaming the Democrats for the worst rate of inflation in three decades in 2022.

Harris announced a series of policy proposals, including: a $25,000 deposit subsidy for first-time buyers with perfect rental records; tax credits for the builders of new homes; extending a President Biden policy to raise child tax credits from $2,000 to $3,600 per child; a $6,000 tax credit for families with new-borns; a cap on insulin costs at $35; and subsidies for Americans buying health insurance under the Obama-era Affordable Care Act.

The dozen or so policies were largely a continuation of Biden’s broadly progressive economic philosophy, but the proposal that garnered the most attention was Harris’s promise to pass a federal law to ban “price-gouging” by grocery companies.

“I will go after the bad actors and I will work to pass the first federal ban on price-gouging on food,” she said. “My plan will include new penalties for opportunistic companies that exploit crises and break the rules, and we will support smaller food businesses that are trying to play by the rules.”

The price-gouging proposal was seized on by Trump, the Republican nominee, as “communist”, implying state-controlled price caps. More surprising was the fury of the liberal and Democratic-adjacent media. The Washington Post ran an opinion piece titled When your opponent calls you ‘communist’, maybe don’t propose price controls? ; the Financial Times said Harris’s plan had put the party on the “defensive” after weeks of positive momentum because the policies were “poorly received”, implying some loss in the polls days after the speech.

Yet the supposed backlash against Harris was not from voters but rather those in the economics profession, who interpreted her vague, two-sentence plan as meaning the introduction of sweeping price controls. Many economists took to social media to decry a “populist and “horrible” policy that would undermine market functioning.

The reaction was entirely disproportionate to what Harris had said or, more accurately, what she didn’t say. She did not propose price controls, with a campaign statement adding that the plan was to “set clear rules of the road to make clear that big corporations can’t unfairly exploit consumers to run up excessive corporate profits on food and groceries”.

This makes the near-universal ire of the economics profession more baffling, particularly as Harris is merely continuing the anti-monopoly rhetoric of the Biden administration, which over the past two years has pinpointed concentrated sectors as being partly responsible for high inflation. The administration has attacked grocery groups for exploitative practices and in 2022 it passed a law to forcing shipping companies to reduce their prices after the pandemic. Equally, Harris’s plans to cap the price of insulin, also announced last week, was hardly decried as communist.

Her federal-level price-gouging ban is also far from revolutionary. Similar state prohibitions against companies yanking up prices during emergencies, usually defined in the range of 10 per cent or more, already exist in states such as Texas, California and New Jersey.

Rather than jumping to conclusions about her anti-capitalist instincts, economists and the media should be pushing the Harris team for details on their definitions of price-gouging and what they deem to be sufficient “penalties”.

What is clear is that both Republicans and Democrats, along with America’s voters, have grievances against the market power wielded by big corporations. Countless examples of egregious corporate pricing include findings from the powerful Federal Trade Commission in March that some food companies had “accelerated and distorted” supply chain disruptions, using them as “an opportunity to further hike prices to increase their profits”.

The FTC is also investigating Amazon, which is alleged to have used a secret algorithm to see how far it could increase prices and force its competitors to follow. Authorities also have investigated cases of price-fixing in sectors such as meat, hotels and energy. Far from being unpopular, polling consistently shows Americans support more aggressive anti-monopoly and anti-trust action.

Pinpointing the role played by corporate pricing power in driving up inflation is one of the big economic debates of the day, one not confined to the United States. The European Central Bank, which manages inflation across the 20 economies that use the single currency, has pointed to “greedflation” in the corporate profit margins of some industries as contributing to its inflation problem. In Britain, there has been less evidence of mass profiteering, with the Bank of England choosing to describe the food sector as engaging in margin “rebuilding” when grocery inflation came close to 20 per cent last year.

Economists who advocate for state monitoring and anti-trust intervention to prevent forms of price-gouging argue that the inflationary episode that spanned 2021-23 shows that markets cannot always and entirely be relied on to adjust outside of “normal” times. In particular, companies that begin to charge more in times of high demand or supply chain disruption add to socially punishing inflation in key utilities such as food and energy. The decisions to impose windfall profits on energy producers in Britain and across Europe are testament to this. Isabella Weber, a German economist who has pioneered the academic study of this “sellers’ inflation”, argues exactly this point, that relying on markets to adjust while prices soar is an abdication of policymakers’ responsibility.

As for Harris’s promise, her price-gouging plans may come to naught, but the scrutiny of corporate pricing behaviour is to be welcomed.

Mehreen Khan is Economics Editor of The Times

Post Comment