Cohort leads new generation preparing for the battles of tomorrow

Attack drones are flying over Ukraine, Gaza and Israel, unmanned undersea vessels are prowling the Taiwan Strait and ballistic and hypersonic missiles are being fired on the shipping lanes of the Red Sea. The technology of war is getting ever more futuristic.

Meanwhile, since the end of the Cold War, the threat of global conflict has been never higher. It has prompted the biggest increases in defence spending around the world in a generation. And what nations are or will be fighting against is rapidly evolving.

On the outskirts of the sleepy North Devon town of Barnstaple, an industrial unit is expanding as it finds its proprietary technology suddenly in high demand. This is the home of SEA, or Systems Engineering & Assessment, a naval technology business in a locality that includes the Appledore shipyard and a Royal Marines base on a site used for preparations for the D-Day landings.

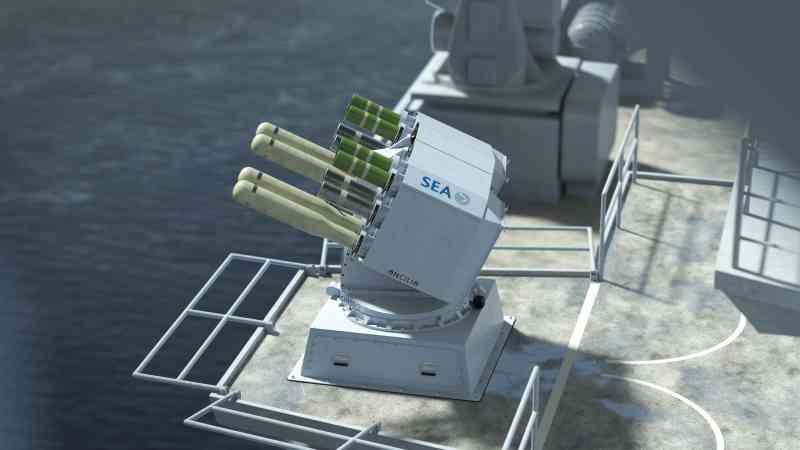

SEA is building surface ship torpedo launchers for naval as well as merchant vessels, as well as state-of-the-art, 150m-long, lightweight sonar arrays called Krait (as in the sea snake) designed to be towed by submarine-spotting underwater drones or by other small spy vessels. Its most eye-catching work, though, is on Ancilia, a freshly minted anti-ballistic, anti-hypersonic missile system, on order with the Ministry of Defence, to be deployed on Royal Navy frigates, and destined for export to navies in southeast Asia uncomfortable with the regional aggressiveness of China.

Ancilia is the name of the 12 sacred shields, a gift from the gods, to protect the sovereignty of ancient Rome. Ancilia, the SEA machine, is a fast-swivelling, turret-like countermeasures launcher, firing off radio frequency or electromagnetic effectors and heat and light pyrotechnics that act as decoys to deflect, divert and maybe detonate incoming superfast missiles. It is designed to take out the sort of missile or multiple missile attacks that now arrive in seconds rather than the several minutes’ warning that warships may have had in the past. Each machine has a dozen launchers for various-sized ordnance, hence the name.

Chess Dynamics, a sister company to SEA based in Horsham, West Sussex, has developed technology to identify and take down aerial drones. Deploying heat-seeking cameras and sensors to locate and track signals used to control unmanned aerial threats, it can disable drones using radio frequencies or it can be fixed to the turrets of armoured vehicles, which can shoot them down.

The financial results of Cohort, the Aim-listed parent company of SEA and Chess, indicate that demand is rising for the group’s technologies. Last year and for the first time, Cohort’s revenues and profits rose above £200 million and £20 million, respectively. Its £135 million MoD contract for Ancilia (for which it beat off competition from Elbit, of Israel, Safran, of France, and Rheinmetall, of Germany) takes the order book to a record near-£600 million, split evenly between Britain and overseas security forces. Its shares, rising steadily towards 900p and valuing the company at more than £350 million, have never been higher.

Andy Thomis, Cohort’s chief executive, sees all that as a validation of a business model for a collection of independent defence technology businesses . The company has six in all, including in Germany and Portugal. It has aped what was achieved on a larger scale by Cobham and Ultra Electronics, British companies latterly taken over and dismantled by American private equity.

According to Richard Flitton, the managing director of SEA, Cohort’s products are the antidote to a new world of unconventional, asymmetric warfare in which opposing military forces have wildly differing capabilities. “The Ukraine situation has shown that a country like Ukraine with neither navy nor air force can take out Russian battleships,” he said. “We are in a world in which the threats are innovative, ad hoc and unsophisticated.”

Cohort, with a highly skilled workforce of 1,300, is less than two decades old. Through a buy-and-build strategy, it has acquired old British and European military industrial capabilities and through research and product development is delivering hardware and software for the second quarter of the 21st century.

It was created by Thomis, 60, and his old boss from their days at the Alvis armoured vehicle company, Nick Prest, 71, Cohort’s chairman. When Alvis was taken over by BAE Systems, they quit and identified the opportunity to create, list and grow a technology company similar to QinetiQ, which had just been privatised. Stanley Carter, the founder of SCS, the defence consultancy, had the same idea. They transacted, raised money and floated Cohort as an acquisition vehicle. Carter, now 82, remains Cohort’s largest shareholder, with a 21 per cent stake.

“All our businesses have the technology needed for the threats that have become apparent,” Thomis said, citing UK border protection and the underwater threat of marauding vessels off the country’s shores. “We know the threat of Putin does not end with Ukraine. We know that when Britain was focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China was amassing a massive fleet, which has galvanised southeast Asia [the Philippines and Indonesia] and Australia and latterly Japan. We know that the Middle East has always been a volcano, eruptions from which we are currently going through.”

Paraphrasing the old generals’ adage, Thomis says tactics and strategy don’t win conflicts, but logistics, getting the right hardware and technology in the right place, does. “This has accelerated demand from our customers and our growth to record results,” he said. “None of us wants to be in a dangerous conflict, but Cohort can contribute to nations’ safety and security.”

Post Comment